Our Foundation is Our Future

What we know as the Smithsonian in the 21st century—with education programs, interactive displays, and robust global research—is a far cry from its cousin of the mid-19th century. And yet one thing has remained constant: a commitment to James Smithson’s dream of “an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” This mission has made the Smithsonian unique in the world, an extraordinary uniting of research, education, conservation, and public trust.

For our 175th anniversary, we celebrate how far we’ve come, the people we serve, and the incredible opportunities that lie ahead of us.

175th anniversary

The Smithsonian: An Engine of the Future

English scientist James Smithson wrote his will in London in 1826, leaving his fortune to the United States to found an institution dedicated to “the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” It was an optimistic, forward-looking, universal vision born of the Enlightenment and the promise of America. Though Smithson never visited the USA, he admired its commitment to democracy and knowledge—two forces enabling human progress.

That vision has always motivated the Smithsonian. Established in 1846, it soon led research in new disciplines like anthropology and meteorology, shipping scientific reports to scholarly societies worldwide.

Today, Smithsonian research reaches millions who visit our national museums and traveling exhibitions and read our popular magazine. We explore the origins of the universe, the sustainability of life on the planet, the full diversity of American history and human creativity. And increasingly, we share our knowledge digitally, connecting with people around the globe. In this way, for 175 years and beyond, the Smithsonian has provided the public with the tools to understand the future, and hopefully, to shape it for the better.

Image: The Smithsonian’s international exchange service annually sent scientific publications to thousands of organizations around the world.

175th anniversary

Saving Species for Tomorrow

The Smithsonian was conceived as a repository of many collections. One was of animal remains. William Hornaday, a Smithsonian taxidermist, sought to observe living bison in order to make his displays more life-like. The animals had been hunted almost to extinction, but he found a few out West and brought them back to Washington. Living and cared for in a pen just outside the Arts + Industries Building, they were a hit with visitors, and formed the basis of the National Zoo, with Hornaday as director. Hornaday went on to become the director of the Bronx Zoo and a leader in the movement to conserve species. Yet during his tenure, a Mbuti (Congo Pygmy) man named Ota Benga was put on display alongside monkeys – a reminder that even progressive-minded people in the past, like Hornaday, had very different attitudes to our own.

Starting in the 1980s, scientists at the National Zoo and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute pioneered methods of reproduction for endangered species – most famously, giant pandas. With the planet losing more and more species every year through loss of habitat, poaching, and environmental degradation, the Smithsonian has played an increasingly important role in preserving species for generations to come, from African and Asian elephants to tropical frogs in Central America. We are also pioneering new technologies for maintaining biodiversity like cryopreservation, in which DNA specimens are kept frozen in biobanks for potential repopulation in the future.

Image: American bison graze on the Mall behind the Smithsonian Castle in the late 1880s.

175th anniversary

Future Flight

Samuel Langley, an astronomer and inventor interested in the physics of flight, became the Smithsonian’s third secretary in 1887. His research resulted in a steam-powered, unmanned aircraft called the “aerodrome” that catapulted from a boat on the Potomac River and flew for over a mile—a record in 1896. He had a shed constructed in the yard adjacent to the Arts + Industries Building to conduct his experiments. Langley next tried to build a manned aerodrome, but it failed to fly, crashing into the Potomac. The Wright brothers succeeded in making the first manned flight at Kitty Hawk just nine days later.

The Langley aerodrome and the Wright flyer were later displayed inside the Arts + Industries Building. In the 1960s, the building was the site of “Rocket Row,” prior to the opening of the National Air and Space Museum (NASM). When the museum opened in 1976, a lunar lander module like the one that had landed on the moon was put on display. One of the mission’s astronauts, Michael Collins, was NASM’s first director. More recently, the museum’s geologist John Grant planned the daily movements of the Mars Rovers Spirit and Opportunity. As one of the most well-attended museums in the world, NASM continues to inspired many young visitors to become pilots and astronauts, engineers and designers.

Image: Rockets are lined up outside of the Arts & Industries Building in the 1960s

175th anniversary

Discovering the Mysteries of the Universe

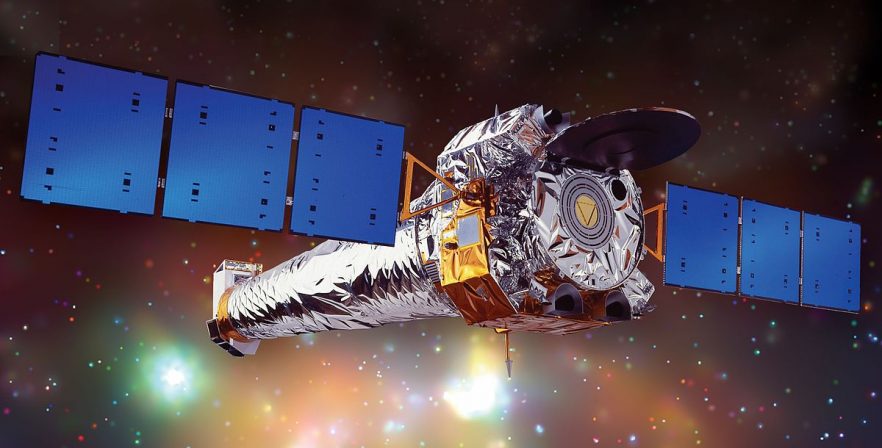

During the Congressional debates about James Smithson’s bequest, which established the Smithsonian, former president John Quincy Adams argued the money should be used for an astronomical observatory with telescopes, which he called “lighthouses of the sky.” Ever since, Smithsonian scientists have pursued knowledge about the universe, the stars, sun and planets. In the late 19th century, the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) set up telescopes behind the Castle and in field camps to observe eclipses and other phenomena.

In 1956, SAO moved its headquarters to Cambridge to work closely with the Harvard College Observatory. There the Center for Astrophysics was established, now one of the largest research organizations of its kind. Its work includes scientific, engineering and mission direction on space satellites, and Earth-based telescopes on the big island of Hawaii, in Chile, Greenland, and Arizona. Smithsonian museums also collect and study historical telescopes, meteorites, and moon rocks. Today, SAO scientists like Margaret Geller, Shepard Doeleman, and Mercedes López-Morales are continuing to study the formation of the universe, the physics of black holes, and search for life beyond our planet—pursuing answers to some of the greatest mysteries.

Image: SAO leads the scientific team for the Chandra X-ray Observatory, launched into space in 1999.

175th anniversary

Preserving Heritage for the Next Generation

Among the early collections to come to the Smithsonian were those from the U.S. Exploring or Wilkes Expedition, which included thousands of ethnological objects, and the Historical Relics Collections, associated with the founding of the United States. The collections grew enormously with acquisitions from the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 and the building of the U.S. National Museum (today’s Arts + Industries Building). Conservation standards were inadequate, however, and lagged behind those in Europe. When the Star-Spangled Banner came to the Smithsonian in 1907 it was actually hung outdoors on the façade of the Castle!

In 1932, the Freer Gallery of Art established the Smithsonian’s first conservation studio, based on methods pioneered at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum. Rutherford Gettens came from Harvard to the Freer Gallery and established a Technical Laboratory, which evolved into its Department of Conservation and Scientific Research. Over the decades, the Smithsonian developed its Museum Conservation Institute, the Lunder Conservation Center, and studios and labs in most of its museums.

In the past decade, the Smithsonian has also worked with partner organizations to save cultural heritage endangered by natural disaster and human conflict—such as in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake, in Iraq following ISIS terrorism, and in the U.S. following regional floods and hurricanes. With heritage increasingly at risk due to conflict and climate change, the Smithsonian works with government agencies, international organizations and local museums to preserve endangered artistic and cultural treasures for the benefit of future generations of storytellers.

Image: The Star-Spangled Banner hangs from the Castle in 1907.

175th anniversary

Understanding Biodiversity, Evolution and Adaptation

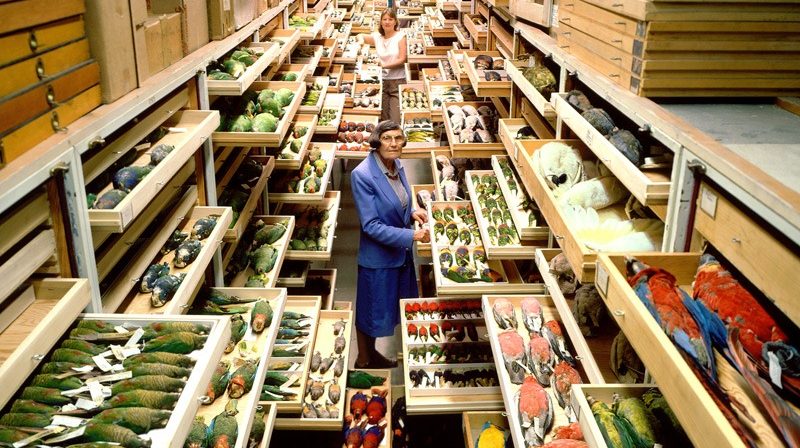

As a young man, Spencer Baird corresponded with the famed ornithologist John J. Audubon, and was influenced by his documentation of American birds and their habitats. Baird formed his own collection and became the Smithsonian’s very first curator. Following the 1876 U.S. Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Baird arranged for items displayed there—filling 62 railroad boxcars—to come to the Washington DC, where a new U. S. National Museum – today’s Arts + Industries Building – was built to display them.

Over the next century, the Smithsonian’s collections of flora and fauna became key to the classification of species and scientific understanding of evolution and adaptation. The Smithsonian now preserves more than one hundred-twenty million specimens and, with the advent of genomic studies, provides a basis for better understanding life on the planet.

Smithsonian scientists at the National Museum of Natural History, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Center, the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and the National Zoo/Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute continue to discover new species. Through collaborative studies of the world’s forests and marine life, these researchers document climate change and its impact on species. And through initiatives such as Earth Optimism, the Smithsonian explores with numerous partners viable ways to mitigate and reverse the depletion of world’s biodiversity to help ensure the future health of the planet.

Image: Collections of bird species are displayed in the National Museum of Natural History.

175th anniversary

Artistic Innovation

The Smithsonian has been supporting contemporary art for 175 years. It already included a gallery when founded, located in the Castle. Among the early acquisitions and exhibitions were paintings of Native Americans by John Mix Stanley and George Catlin’s “Indian Gallery.” These early collections were the predecessors to the current Smithsonian American Art Museum, which together with the National Portrait Gallery occupies the former U.S. Patent Office – called by Walt Whitman “that noblest of Washington buildings.”

Other Smithsonian art museums grew in a disparate way. Charles Lang Freer gave his collection of Asian art and works by James Whistler, along with funds to construct the Freer Gallery of Art. Both the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and the National Museum of African Art were originally private institutions, transferred to the Smithsonian in 1968 and 1978 respectively. In 1974, the Hirshhorn Museum opened, giving the Smithsonian a world-class venue for contemporary art. Its founding collection came from Joseph Hirshhorn, who came to the US from Latvia when he was six years old. He considered his gift “a small repayment for what this nation has done for me and others like me who arrived here as immigrants.”

Because of the Smithsonian’s broad founding vision, art can be found all across the Institution: scientific illustration in the Natural History Museum, industrial arts and photography in the National Museum of American History, stamp art in the Postal Museum, and the NASA space-age art collection in the National Air and Space Museum. Reflections of future thinking are present throughout, testifying to artists’ important role in envisioning new ways looking at and understanding the world.

Image: Nam June Paik’s Electronic Superhighway, 1995, in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

175th anniversary

The Future of Medicine

Given the terrible toll taken by the Covid-19 pandemic, the importance of understanding and preventing diseases in the future is clearer than ever. The Smithsonian has devoted itself to this cause since the days of the Civil War, when it acquired patent models for surgical tools and artificial limbs – all too common during a conflict that resulted in so many deaths, injuries and amputations.

Collections have since grown to encompass nearly all aspects of health and medical practice: early X-ray apparatuses, the penicillin mold from Alexander Fleming’s experiments, Jonas Salk’s original polio vaccine, the first artificial heart implanted in a human, and panels from the AIDS Memorial Quilt, a moving example of cultural response to disease. Recently the Smithsonian has acquired materials relating to the work of Nobel Prize winner Kary Mullis, whose Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) technique allows for the replication of DNA so crucial to contemporary medical diagnosis and treatment. And exhibitions like Outbreak at the Natural History Museum help to spread this knowledge, educating visitors about pandemics.

Smithsonian researchers are also making huge contributions. The National Mosquito Collection (including 1.9 million specimens) helps us understand the evolution of viruses. Scientists at the Tropical Research Center in Panama have worked to prevent Zika, and those at the National Zoo have studied Avian flu. Suzan Murray, a scientist and veterinarian, heads the Smithsonian’s Global Health Program, working with U.S. and international agencies to track the movement of infectious diseases from animals to humans. In April 2020, Smithsonian scientists studying bats in Southeast Asia identified six new coronaviruses.

Image: Smithsonian collections include the original Salk vaccine for polio.

175th anniversary

Representing the American Story

When the great Black orator Frederick Douglass was invited to speak at the Smithsonian in 1862, debating the abolition of slavery, Secretary Joseph Henry refused to allow it: “I would not let the lecture of the coloured man to be given in the rooms of the Smithsonian.” Henry did believe it important to document the cultures of American Indians, but mainly because he thought they would “disappear.” Smithsonian curators also refused to collect material documenting the women’s suffrage movement, only relenting with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

Not until the middle of the 20th century – in response to mounting criticism – did the Smithsonian began to become more inclusive, with programs like the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. In 1989 Congress established the National Museum of the American Indian, including provisions for the repatriation of human remains and cultural objects to Native communities. Led by founding director W. Richard West, a member of Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, the new museum opened on the Mall in 2004 highlighting Native voices and illustrating the richness and diversity of their cultures.

There was, and still is, much progress to be made. A 1994 report noted the Smithsonian’s “willful neglect” of Latino history and culture, and a similar report a few years later pointed to lack of regard for Asian-American stories. Congressman John Lewis’ annual appeal to create an African-American museum was repeatedly rejected by Congress until 2003, when President George Bush at last signed bipartisan legislation for its establishment. Led by founding Director Lonnie Bunch, the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in 2016 to critical acclaim.

In recent decades the Smithsonian Latino Center, and Asian Pacific American Center have grown. The Smithsonian has acquired collections documenting gay and lesbian culture, and the history of disability. Smithsonian museums, including the National Portrait Gallery, have increased the representation of art by and of women. Bunch was appointed Secretary in 2019 –the first Black Secretary of the Smithsonian. Most recently, in January 2021, legislation authorized a Latino museum and a Women’s History museum. The Smithsonian is increasingly committed to helping Americans bridge their differences by presenting a fuller view of their history.

Image: The Red Chador, a performance by Anida Yoeu Ali with Studio Revolt, organized by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center was presented at the 2016 Crosslines program in the Arts + Industries Building.